Bringing food science to the public

Mathilde Touvier helps shape the conversation around science and public health. She provides tools for informed food choices and advocates for policies that aim to make healthier options more accessible to all.

‘Everyone makes daily food choices, wondering what to eat or what to feed their children. Over a lifetime, we consume around 30 tonnes of food and 50 000 litres of drinks, exposing ourselves to dozens of food additives every day. With growing public concern about nutrition, health, and food safety, the need for reliable, science-based information has never been greater.’

One in five deaths worldwide is linked directly or indirectly to nutritional factors, and more than 40% of cancers could be prevented by changing our lifestyle, says Touvier.

‘Our research, based on the NutriNet-Santé cohort study on >100 000 participants, has identified links between ultra-processed foods and certain food additives (such as nitrites, emulsifiers, and sweeteners) and an increased risk of several chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. While traditional nutritional factors such as saturated fat, sugar, salt, and lack of dietary fibre remain fundamental, it is also crucial for the public to be aware of the risks associated with the consumption of these ultra-processed foods and their additives.’

Food trends dominate social media, but much of the information shared is misleading. ‘Nutrition and health are subject to an overwhelming amount of fake news, spread by charlatans and commercial websites. These false messages are amplified by the agri-food industry's aggressive marketing, which encourages people to consume ultra-processed products that may not always be beneficial to their health.’

It is crucial for the public to be aware of the risks associated with the consumption of ultra-processed foods and their additives

‘One of our initiatives was working with children at the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie, where we invited them to build models of our research using Lego bricks, sparking conversations about food and health in a fun and creative way. We also teamed up with the not-for-profit organisation Open Food Facts, which offers a smartphone app that lets users scan food barcodes to find detailed product information, including additives, helping people make more informed choices.’

‘One of our initiatives was working with children at the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie, where we invited them to build models of our research using Lego bricks, sparking conversations about food and health in a fun and creative way. We also teamed up with the not-for-profit organisation Open Food Facts, which offers a smartphone app that lets users scan food barcodes to find detailed product information, including additives, helping people make more informed choices.’

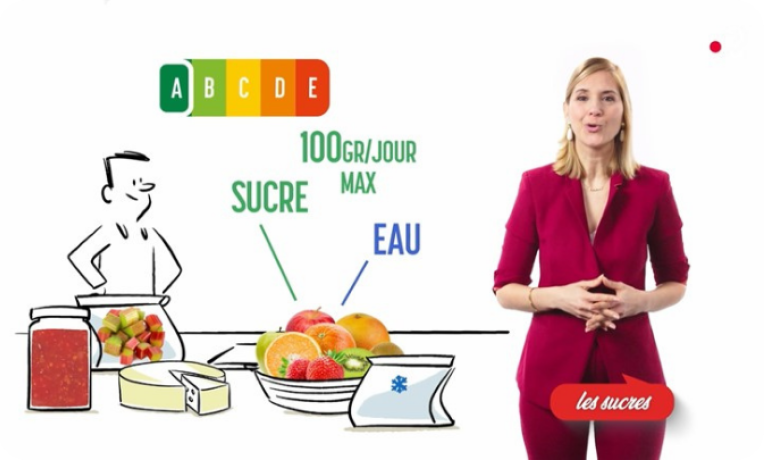

Perhaps one of the most visible results – at least in seven European countries – is the Nutri-Score label, a 5-letter, 5-colour logo on the front of food packaging that offers at-a-glance information about the nutritional quality of food. The findings of her ERC-funded project contribute to the evolution of Nutri-Score’s algorithm, which for instance, since 2024, includes a penalty for drinks containing artificial sweeteners.

Perhaps one of the most visible results – at least in seven European countries – is the Nutri-Score label, a 5-letter, 5-colour logo on the front of food packaging that offers at-a-glance information about the nutritional quality of food. The findings of her ERC-funded project contribute to the evolution of Nutri-Score’s algorithm, which for instance, since 2024, includes a penalty for drinks containing artificial sweeteners.

The adoption of Nutri-Score as Europe’s mandatory label is currently under discussion, with the OECD estimating it could prevent 2 million chronic disease cases by 2050.

‘Publications in major medical journals have led to regular invitations to hearings with policymakers, including the French National Assembly, the UK House of Lords, and the WHO. I am also in close contact with the French Ministry of Health to discuss how this research can guide public nutrition policies.’

I avoid guilt-tripping messages and emphasise that no food is forbidden

Given the powerful lobbies undermining public health messages, Touvier ensures her research is accurately presented in the media. ‘It’s crucial to explain how public health nutrition research works, how scientific evidence is built, and how we distinguish between validated recommendations and new studies with uncertainties. The public can understand this nuanced approach if we take the time to explain it.’

Touvier adds that she is often accused of being ‘liberticidal’— restricting personal freedoms by telling people what to eat. ‘Ironically, our research aims to empower people by identifying diet risks so they can make informed choices. What truly limits freedom is the marketing that encourages unhealthy food consumption without us even realising the risks. When it comes to dietary recommendations, I avoid guilt-tripping messages. I present things positively, explaining that no food is forbidden, and that occasional consumption of ultra-processed food or foods with poor nutritional profile won’t necessarily lead to health problem. It's all about frequency and quantity.’

Public outreach is ‘an extremely rewarding and enjoyable experience’, Touvier says. ‘You come face to face with real life, see the impact of your research, and hear people's concerns, which inspire future projects. For me, this is the true purpose of my public health work and the reason I chose this fascinating profession. Besides, if we don’t engage in public communication, others—sometimes less well-intentioned—will fill the void, spreading unvalidated information. It’s our role as researchers to place science at the centre of constructive, rigorous, and caring communication, guiding society in the right direction.’

Biography

Biography

Mathilde Touvier is a graduate of AgroParisTech and Doctor in Epidemiology and Public Health. After 6 years at the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (ANSES) and 1 year as visiting researcher at Imperial College London, she joined the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team EREN (U1153 Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord & Paris Cité Universities/ NACRe network), of which she became Director in 2019. She is the principal investigator of the NutriNet-Santé cohort study (180 000 participants, 2009-ongoing). She was Professor in Public Health at the College de France in 2022-2023. Her ERC Consolidator Grant project ADDITIVES is on the health impacts of food additives.