Editorial – Why public engagement with research matters

The importance of public engagement in research cannot be overstated in an era where scientific advancements shape our world. The ERC’s Public Engagement in Research Award (PERA) plays a significant role in encouraging ERC-funded researchers to share their work with the public, demonstrating science's relevance and challenging scientists to communicate accessibly.

Interestingly, we've shifted from ‘communications’ to ‘public engagement’ – a much better term reflecting active public involvement, not just information sharing. This shift challenges the outdated ‘ivory tower’ mindset some researchers held, viewing public involvement as unnecessary or distracting.

Last year's PERA saw impressive participation across diverse projects. Some naturally aligned with public engagement, while others did not, making their involvement even more notable. A standout winner was a wave technology project set in the Aran Islands, Ireland, which exemplified true engagement, with the entire community involved in experiments. It is remarkable to see the public not just observing but actively participating in science. Some scientific fields naturally lend themselves to public engagement more than others. Immunology, for example, found a receptive audience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, topics related to the natural world or climate change often resonate easily with the public.

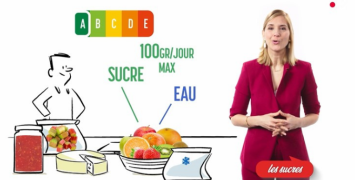

However, communicating less intuitive concepts is far more challenging. The key is finding relevance in everyday life – I recently saw a mathematician explain how to prevent coffee spills from a mug while walking across the kitchen, using mathematical principles. It's about making abstract concepts relatable.

For me, discussing my work has always felt natural, even chatting about it with friends in the pub. While not everyone is comfortable with public engagement, most scientists can learn to communicate effectively with some effort. It's incredibly rewarding – people are often genuinely grateful when you explain complex concepts clearly.

My most rewarding experience was during the Covid-19 pandemic, providing regular radio updates. The public's gratitude was overwhelming – they appreciated having complex information made accessible. This period highlighted the power of effective science communication when public interest peaks.

Today, it is more critical than ever for scientists to engage with the public, especially in an era of widespread misinformation. We must present facts clearly and honestly, offering reliable information sources. It is also an opportunity to illustrate the scientific method itself – our most powerful tool for understanding the world.

As we move forward, it is essential for public engagement to become an integral part of scientific practice. Initiatives like PERA, with their high-profile presentation that adds a sense of glamour - much like the Oscar’s - not only recognise excellence in this area but also inspire the scientific community. For younger scientists, such as ERC Starting Grant holders, it is important to develop strong communication skills early in their careers. In some universities, it is now a factor in promotion decisions.

Furthermore, improving public communication skills also enhances the ability to explain your work to fellow scientists. Any practice in communication helps, and those skills translate directly into professional interactions. In this sense, public engagement is not just a way to give back to society – it is an opportunity for growth as a scientist.

Beyond public outreach, there is also much value in communicating with policymakers. If scientists can articulate real-world benefits of their work, it strengthens the case for continued research investment. Recent surveys show high trust in science across Europe, with many supporting a greater role for scientists in policymaking. This too is a form of engagement worth fostering.

Public engagement in science isn't just about distributing information; it is about building bridges between the scientific community and society. As more researchers embrace this challenge, we can look forward to a future where scientific discoveries are not just made but also understood and celebrated by all.

Luke O’Neill, ERC Scientific Council Member