To communicate or not to communicate… is that the question?

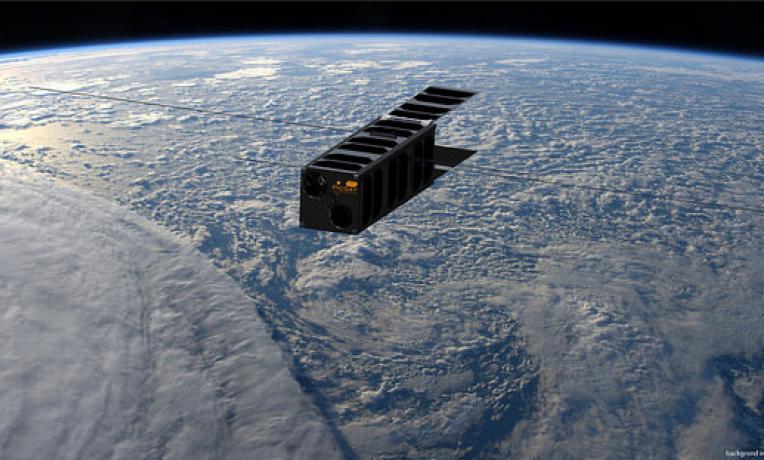

10..9… 8…7… Sylvestre Lacour and his team members watch the screen nervously. They smile, but you can feel the tension in the room …6…5…4…It's still night outside and the air is frozen at the Paris Observatory. In the silent room, a female voice continues the countdown…3..2…1… On the screen, beneath the Indian rocket, the shy sparkle has now become an impressive flame. A round of applause disrupts the last moments of stillness. On the 12 of January 2018, at almost 5 am, PicSat, the brick sized French nanosatellite, flies away towards its orbit around the earth.

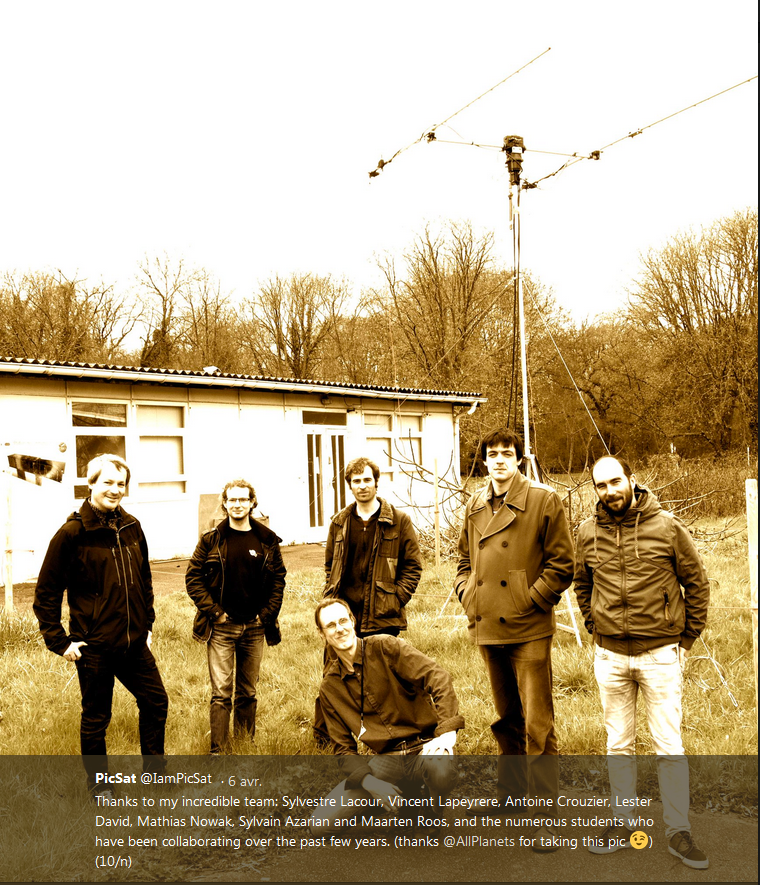

This moment was captured by the camera lens of Marteen Roos, the Communication and Outreach Manager in Lacour's ERC research project. Three months before the rocket launch, he started reporting on the team's activities, tirelessly filming and tweeting about PicSat's last weeks on the ground and first steps into space. He also had the idea to develop a real character for the nanosatellite, who shared in person its hopes, fears, successes and failures with an increasing number of followers.

"I am Picsat. My goal is to observe the star Beta-Pictoris and detect when its young planet and/or exocomets will pass in front of it!" @IamPicsat Twitter account

As in many stories, this particular communication journey was the fruit of both a chance encounter and a specific need. Marteen, a former planet scientist transformed into a film-maker, was shooting at the Paris Observatory. "The connection was good from scratch", confesses Sylvestre Lacour, very conscious at that time of the importance of communication in research. That's how Marteen become a full member of the research team.

His initial mandate was to publicise the project among amateur radio operators around the world. PicSat's mission was to spot the long-awaited transit of Beta Pictoris B in front of its star. To do so, the nanosatellite had to measure very precisely the light of the star and to send this data through radio frequency to the ground station. Yet, the transmission could only take place when PicSat would fly over Paris for about 30 minutes per day. Bringing on board a large community of radio amateurs who could collect this data at any point in time and space, was key for the success of the project.

Telling the story

During six months, PicSat tweeted every single day, more than 1,400 times. He tweeted about itself – or shall we rather say "himself""? – about his journey, about the research team. He posted more than 200 pictures and videos; he even sang and recited small poems. He was never controversial but took the liberty to comment on science related topics, mostly on planets and starts, and even on the passing of Prof. Stephen Hawking. PicSat became so popular that the initial target audience of radio amateurs soon became a much wider one, from kids, to journalists and citizens at large.

Actually, PicSat told us a story, and that was the key for success. As a fully rounded and appreciative character, he engaged emotionally with its audience. We could feel the tension before a test, the joy after each new successful step and the great disappointment following failure. Certainly, the real heroes behind this adventure were Sylvestre Lacour and his team members: Vincent Lapeyrere, Antoine Crouzier, Lester David, Mathias Nowak, Sylvain Azarian and Maarten Roos.

PicSat's journey was chronicled according to a simple but precious principle: transparency. "From day one", explains Marteen Roos, "I was struck and inspired by the transparent and honest communication within the team. We could discuss all aspects of the project and express our views. Communication towards the outside followed the same principle."

PicSat therefore became an honest and chatty character. He remained positive at all stages of the project and communicated, with full openness, on situations of stress and difficulty. He even apologized when things started to go wrong…

At all times

On 20 March, PicSat lost his radio voice. After 10 weeks of operation in space, he stopped transmitting data and the system could not be rebooted. Through Twitter, he continued to interact with his followers, providing news on the latest tests and rebuttal attempts. He also thanked followers for the many messages of encouragement received and published a good bye message from the project team after the difficult decision to call an end to the mission, on 5 April.

PicSat could not reach its full scientific goal and record the transit of Beta Pictoris B – no one could in the end. However from a communication perspective, his mission was accomplished. The public engagement was rich, beyond the community of radio operators - Sylvestre Lacour even received a set of drawings of PicSat made by children from an elementary school. The international media coverage on press, television and radio was also impressive, following the orchestrated action of the various partners involved in the project, including the ERC.

Interestingly, it was the journey that created the engagement rather than the outcome. This is probably because many people are genuinely interested in science and the full process behind it, made of passion, resilience, risk, serendipity, failure and sometimes success. From that perspective, the dilemma is not that much about communicating or not communicating about your research, but rather about choosing the right angle to tell your story. The ERC is here to help.