Effective targeted treatment for hairy cell leukaemia

An ERC-funded project is conducting groundbreaking research into a rare form of leukaemia, proving the effectiveness in patients of non-chemotherapy-based treatments that target the genetic cause of the disease. The Hairy Cell Leukemia project, launched by the Institute of Hematology at the University of Perugia in Italy with funding from the European Research Council, is one of the world’s foremost initiatives to develop a targeted therapy for hairy cell leukaemia (HCL), a rare form of blood cancer.

HCL accounts for about 2% of all leukaemias worldwide, with around 1 500 people diagnosed each year in the EU. Its rarity means that it has been the focus of relatively little research since the late 1990s, when chemical compounds called purine analogues were found to be effective in treating it chemotherapeutically, albeit with some severe side effects for patients.

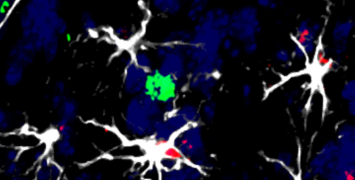

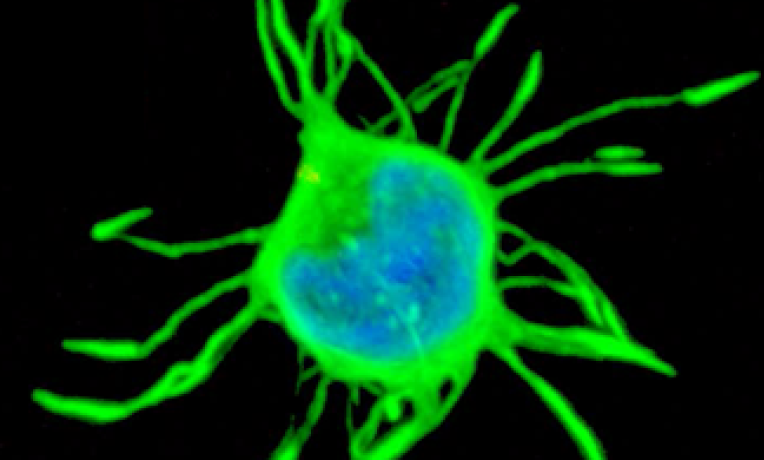

“Hairy cell leukaemia is a unique and very interesting form of cancer that derives its name from the unusual hair-like projections that the cancerous cells develop,” explains Prof. Enrico Tiacci, who received an ERC Consolidator grant for his project. “Even more remarkably, HCL is unlike most other forms of cancer in that it is not genetically heterogeneous: in almost all patients, HCL exhibits the same mutation of the BRAF gene, which controls cell growth.”

That genetic homogeneity and simplicity is also HCL’s Achilles heel, Tiacci and his mentor Brunangelo Falini at University of Perugia discovered. Since first identifying a BRAF mutation known as V600E as being involved in HCL development, Tiacci and Falini have focused on how to target the disease with a non-chemotherapy-based, genetics-driven and rationally designed treatment strategy. They turned to a drug called vemurafenib that inhibits BRAF, and which was being developed by pharmaceutical group Roche.

Designed to treat melanoma, an unrelated form of skin cancer often carrying the same BRAF mutation, vemurafenib is extremely effective in vitro against HCL, reversing the gene expression that distinguishes HCL cells from the cells of other blood cancers. Furthermore, it causes the cells to lose their hair-like protrusions, eventually killing them, the researchers found.

Towards complete remission in HCL

The team launched a Phase 2 clinical trial in Italy; a similar initiative was then set up by colleagues in the United States, in which late-stage patients who had often undergone chemotherapy repeatedly were treated with tablets of vemurafenib as outpatients for two to four months. The results were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, a highly respected scientific publication.

“Overall response rates to the treatment were 96% after a median of eight weeks in the Italian study and 100% after a median of 12 weeks in the US study, while 35% and 42%of patients, respectively, had a complete response,” Tiacci says.

“These were people who in some cases had been living with HCL for decades and had undergone multiple courses of chemotherapy that had weakened their immune system and their bone marrow function. The drug was not only able to put them into remission, but did so without the toxic effects of chemotherapy, which these patients would not have withstood.”

However, even patients that showed a complete response had some residual leukaemic cells visible in their bone marrow when tested with highly sensitive techniques – a reservoir from which leukaemia can re-grow and cause patients to eventually relapse several months to a few years after being treated. Tiacci says the next step is therefore to try to kill residual leukaemic cells to prevent, or at least further delay, relapse.

Building on the results of their initial trials, the Hairy Cell Leukemia team is now developing a combination therapy in which vemurafenib is administered together with injections of rituximab, an antibody that drives the immune system to attack the hairy cells. Initial results from an ongoing clinical trial in Italy appear promising.

“As we have to buy the drugs in order to conduct this research, the funding we are receiving from the EU is crucial to developing this innovative therapy strategy, which will ultimately save lives and improve quality of life for many HCL sufferers who are failing to respond to conventional treatments,” Tiacci says.

In light of the results so far, Tiacci predicts it is highly probable that a vemurafenib-based approach to treating HCL will be used clinically within a few years after further testing and regulatory approval: “Initially, as a second or third line of treatment in patients that have ceased to respond to chemotherapy, but possibly eventually as a first-line course of treatment that eliminates the need for chemotherapy entirely.”