An international career to push the frontiers of epigenetics

With her degree in biology, Dr Maria-Elena Torres-Padilla left Mexico and embarked on an international career in epigenetics. She completed her PhD at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and then moved to Cambridge University. In 2006 she joined IGBMC in Strasbourg working as a group leader. She has just been appointed Director of the Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells of the Helmholtz Zentrum in Munich. Supported by an ERC grant, she studies the mechanisms controlling embryonic cellular plasticity with the aim of shedding new light on today's fertility issues. In this interview she shares her story as a non-European scientist in Europe.

What motivated you to conduct research in Europe?

Soon after I started spending time in a lab, during my bachelors at the National University of Mexico, I realized that the approach to science differs from country to country, so going abroad was a way to enrich my research work with these different visions.

My first choice, Europe, was driven by my interest for the cultural context as for me it was important to do quality research but also to enlarge my horizons. I went to France because I was interested in the language and history of this country. During my PhD in Paris, I spent some months as a visiting scientist in California and I finally decided to stay in Europe because there is a strong stress on hypothesis-driven research: you have a question, you make a hypothesis and you test its validity. This is the approach I like! Identifying these questions is a continuous, amazing and rewarding challenge. What I really like the most is that there are no limits to knowledge and this idea of pushing beyond the current knowledge has always attracted me!

You said you are “addicted to internationality”: what does mobility bring to a researcher’s career in your opinion?

International mobility is essential. You can learn a lot from experiencing the various approaches to research. You can challenge yourself and give the best. And culturally, it's very enriching. My lab is very international and this is something I am particularly proud of. I have currently 9 team members, coming from Japan, Lebanon, UK, Poland, Hungary and France and I also have a student from Mexico.

Of course, there are the usual difficulties that people moving abroad experience. For example obtaining a visa can be a long process, not only in Europe but also in other continents. In some non-English speaking countries, institutes may not be well equipped to welcome foreigners. It takes some time to learn a new language but, at the end, I think it's feasible. Funding may also be an issue but, for example, the Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions and ERC grants are open to applicants from any nationality! I think that when you have a clear idea of what you want to do and where you want to go, problems can be sorted out. Things have improved a lot since I arrived here in 1998, so I would certainly encourage researchers from my country to come to work in Europe!

What decided you to apply for ERC funding?

The size and duration of the grant: you have a hefty financial help, which will be key for what you are going to do for the next five years. And also the prestige, it’s a label of recognition among your peers. Most importantly, the ERC supports curiosity-driven research approaches. I wish there were more tools to promote this principle in Europe, at least in the field of epigenetics!

Your research could help understand key processes in human reproduction. Could you explain how?

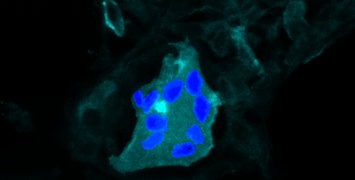

We study the mouse embryo at the very start of its development. Our research aims to understand how, following fertilization, chromatin (a substance made of proteins and DNA that can be found in the nuclei within the cells) drives the cells from a so-called "totipotent" to a "pluripotent" state. Just after fertilization, the totipotent cells are able to generate the whole embryo, the placenta and umbilical cord. But, in the following stages of cell division, they lose this ability and become pluripotent: they progressively specialise into the types of cells that will form the different tissues of the body.

Over the last years we have applied novel techniques that allowed us to identify a protein complex responsible for maintaining the pluripotent state of cells. By inactivating it, we succeeded to induce cells with totipotent features. This result could lead to applications in regenerative medicine and a better understanding of human fertility troubles.

Fertility problems in Europe are very common: 50%-60% of fertilized eggs do not succeed to implant - the woman is not even aware of it. So, what makes the embryo suitable for implantation? With our research, we can help to answer this question and contribute to prevent the problems of implantation in the future.

What do you plan to do next?

There are a number of burning questions to pursue scientifically, to deepen more the secrets of cellular plasticity. In addition, from next year on I will have the possibility to mentor junior group leaders, which is a unique opportunity as the mentoring part of my work is very rewarding. I have also been interested in becoming part of Science Policy discussions groups across Europe, as I think this is also a very important endeavour for the future generations. And I want to pursue my research with the support of an ERC Advanced grant, hopefully in a couple of years!