In search of Amazon’s ancient hunters

Early migration to South America occurred via a land bridge connecting Siberia to Alaska, when sea levels were significantly lower than today. From there, humans ventured southward, making South America the last terra incognita to be inhabited by humans, other than Antarctica.

José Iriarte conducts fieldwork in the Colombian Amazon, a region of particular interest in tracing humanity's global journey. Evidence of some of the earliest human occupations in the Colombian Amazon can be found in the Serranía de la Lindosa, dating back approximately 12 600 to 13 000 years.

“What sets Colombia apart is its remarkable environmental diversity, encompassing deserts, savannahs, tropical forests, seasonal tropical forests, and mountainous terrain, ranging from sea level to heights of 5 000 meters,” explains Iriarte. “This diversity makes it incredibly compelling to study how humans adapted to new territories and landscapes during a pivotal period marked by the transition from the last Ice Age to the Holocene epoch.”

Ice Age mammals

As an environmental archaeologist, Iriarte explores the past through the study of ancient plants and other vegetation. Among his methods is the analysis of charred plant remains obtained through flotation, a technique that separates these lighter buoyant remains from soil samples. These remnants give him vital insights into early human subsistence strategies.

“Surprisingly, early humans in the Amazon were not big game hunters like the typical hunter-gatherers who arrived in North America, who hunted large Ice Age mammals”, Iriarte explains. “Instead, they relied on a diversified subsistence. They consumed fish, small to medium mammals, and a wide variety of plants, including 13 different palm species. Through botanical analyses, we learnt that the surroundings of Serranía de la Lindosa were once lush tropical forests teeming with resources.”

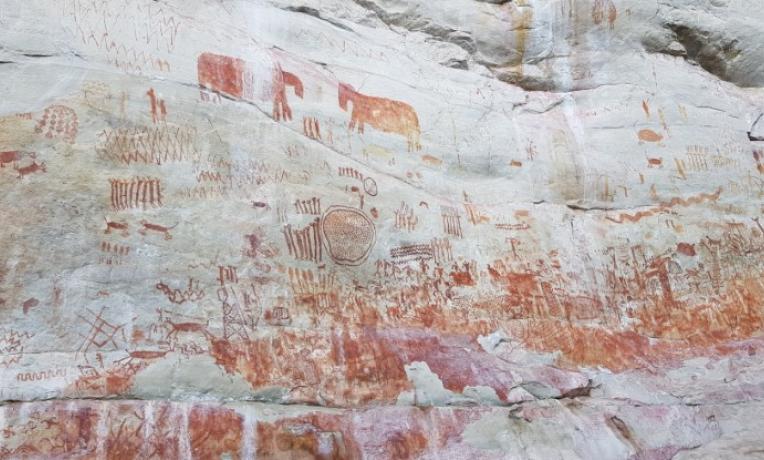

The allure of the region for early humans lay not only in its abundance of resources but also in its varied landscapes. “It is an incredible location because it features transition of environments known as ecotones,” notes Iriarte. “Here, savannahs meet tropical forest, and riverine environments are abundant. Rock shelters in La Lindosa provided shelter, protection, and ideal canvases for painting stories. The origin of the Amazonian cosmovisions is embodied in these walls. The region’s wealth of resources also included raw materials for stone tools.”

Holding hands

Among the LastJourney project’s significant discoveries are a collection of early rock art dating back at least 10 000 years. These artworks vividly depict what are likely Ice Age animals such as mastodons, horses, camelids, and a giant sloth, as well as a diverse array of fish, turtles, lizards, porcupines, monkeys, birds, bats, among others. Additionally, scenes of people dancing, performing rituals, and holding hands are portrayed in other rock paintings. These tens of thousands of paintings adorn cliff faces stretching approximately 12 to 13 kilometres. “These paintings offer profound insights into the lives of early hunter-gatherers”, says Iriarte. “Looking at this rock art is similar to the experience of witnessing Machu Picchu firsthand: just breathtaking.”

Moreover, through an ERC Proof-of-Concept Grant (part of his ERC Consolidator Grant PAST), Iriarte has advanced the use of UAV LiDAR sensors in archaeological research. “These sensors emit laser pulses at rapid intervals”, he explains. “The pulses bounce off objects like the Earth's surface or forest canopy, allowing precise distance calculations based on their travel time. By precisely measuring the time it takes for these pulses to travel to their target and return, the device can accurately calculate distances. This process is repeated hundreds of thousands of times per second, enabling the sensor to create detailed 3D topographical maps of the terrain below.”

Interestingly, many laser pulses penetrate forest canopies. The ability to see through foliage enables archaeologists to spot subtle terrain variations, identifying potential features of interest like ancient settlements, roads, and earthworks. Such detailed information facilitates the planning of ground-based investigations and excavation efforts.

"We use this technology to map archaeological sites with unparalleled accuracy," adds Iriarte. "Previously, achieving similar results required a team of fifty researchers using conventional methods, whereas the laser sensor accomplishes it in a fraction of the time. We were pioneers in adapting this technology for aerial deployment, initially experimenting with small aircraft before transitioning to helicopters. The increasing accessibility and affordability of this advanced remote sensing technology are revolutionising our field work."

Reconstructing ancient climates

The collaboration with Iriarte on his ERC-funded project extends across prestigious research institutions and various scientific disciplines. “Our partnership with the University of Sao Paulo focuses on reconstructing past climates through paleoclimate studies”, he explains. “Collaborating with the Max Planck Institute allows us to analyse isotopes from both megafauna and human remains, shedding light on dietary habits and mobility patterns. By utilising strontium isotopes, we investigate territorial patterns and migration routes. Universidad de Antioquia and Universidad Nacional de Colombia contribute with the analysis of stone tools and plant remains. Meanwhile, the University of Copenhagen contributes its expertise in ancient DNA analysis, particularly from dental remains, aiding in the reconstruction of ancestral lineages.”

“These collaborations represent the extensive teamwork facilitated by ERC grants”, adds Iriarte. “While my previous Consolidator Grant project concentrated on late prehistoric societies, my current project examines the entire human history of the Amazon, highlighting the significant contribution ERC funding makes to interdisciplinary research. A forthcoming open access book titled ‘Archaeology of Amazonia: A Human History’ underscores this continuity.”

Biography

José Iriarte is an archaeologist and archaeobotanist whose research interests are in human-environmental interactions, the development of agricultural economies, and the emergence of complex societies in lowland South and Central America. He is the director of the University of Exeter Archaeobotany and Paleoecology Laboratory and forms part of the Centre for the Archaeology of the Americas and has extensive experience directing international multidisciplinary projects integrating archaeology, archaeobotany, palaeoecology, palaeoclimate, soil science, remote sensing (Lidar), ancient DNA, and modern ecology across Latin America. His work has featured in international media, including BBC, National Geographic Society, New Scientist, and Scientific American, in addition to a Channel 4 documentary ‘Jungle Mystery: Lost Kingdoms of the Amazon.