why is the world green?

Have you ever wondered why our world is green? For decades, the most accepted answer has been that predators control herbivores, allowing plants to flourish. But is that really so? ERC grantee Katerina Sam at the Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences in the Czech Republic is testing novel aspects of this ‘green world hypothesis’ to get a more realistic answer. Her work has important implications for protecting our planet’s biodiversity.

For decades, the prevailing scientific belief has been that our world is green thanks to predators limiting the abundance of herbivores, which in turn allows plants to thrive. But these powerful interactions are not so easy to study, since there are many elements involved. ERC grantee Katerina Sam at the Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences in the Czech Republic has decided to address this complexity by studying the effect of top predators on plants, first individually and then in combination with other predators.

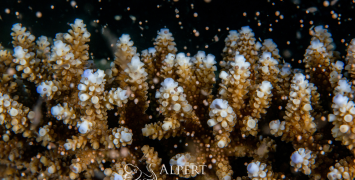

To do so, she has chosen the treetops of forests. These upper layers of forests – also known as canopies – have billions of leaves and are teeming with biodiversity. However, given their height, they are difficult to reach and were up until recently inaccessible to scientists.

Sam’s ERC project BABE is the first one to work on several of the few existing treetop platforms across the globe. ‘It is quite a large intercontinental experiment: we have already collected data in Japan, China and at two study sites in Australia. Nowadays we are working in Papua New Guinea and we also plan to sample in Malaysia,’ she says.

Another particularity of the project is that it aims to measure the effect of individual predators on herbivore insects and subsequently on plants, instead of the predator community as a whole. ‘By protecting the trees with cages that we open at different moments of the day, we can study the effects of birds (who fly during the day) and bats (who do so during the night) on the herbivore communities,’ explains Sam. ‘This way we get a measure of which herbivore insects they eat, or rather, which insects don’t get eaten when these predators can’t get to the tree.’

Watching this video you are accepting Youtube cookies policy

Exciting first results in Japan and Australia

The project is only in its second year but the team already has very exciting results on how predation may service the functioning of the forest. When protecting treetops from birds in Japan’s forests, the damage from herbivore insects increases by around 5-10 %, which will likely have a negative impact on the trees’ flowering and fruiting in the coming years.

In Australia’s forests, on the other hand, preliminary results paint a different picture: when researchers removed the main predator (ants in this case), instead of an increase in herbivore damage, they found spider communities taking over the predator role. These results suggest that predation by birds (in Japan) and ants (in Australia) might provide different eco-services to the functioning of the forest.

These two factors – studying predators individually and doing so in the forest canopies of five different countries – is what positions this project at the frontiers of science. The findings have direct implications for protecting biodiversity. ‘When we see changes in the predator communities, we immediately see changes in the diversity of the herbivore insect community. If a certain predator disappears, the inter-communities and the herbivore activity change, so the effect spreads further in the food web,’ says Sam.

Benefits of winning an ERC grant

Sam is one of several dozen ERC grantees based in the Czech Republic so far. She said winning the grant had a big impact on her research group: ‘It allowed me to recruit many technicians and manage several PhD students, all crucial in such a big project with so many sampling sites and so many taxa to study. Of course recruiting such a big group is possible thanks to the lower salaries and life expenses in Eastern European countries, clearly one of the benefits of doing research here.’

She added that this is only the second ERC grant in her department: ‘Winning it was definitely a big thing. But I must admit it is mainly when I attend a conference in Western Europe that I get the “wow” effect for my ERC grant. Most of the people in the Czech Republic still don’t really know what the ERC is.’

When asked what advice she would give to her fellow researchers in Czechia to encourage more of them to apply for ERC grants, she added: ‘My advice would be that if you have a great idea for a project, just believe in it and go for the ERC! However, when I got my ERC grant some people came to me asking what to write about to get an ERC. This is not how it works – you need to have that really good idea first and then apply with it, not the other way around.’

BIO

Katerina Sam got her bachelor and master degree at the University of South Bohemia in the cognitive ecology of birds. In 2008, a field course in tropical ecology in Papua New Guinea changed her carrier path and she ended up finishing her PhD degree there. During her postdoctoral stay at the Griffith University in Brisbane, she continued her research in this field, and finally returned to the Czech Republic to establish a laboratory of multitrophic interactions at the Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences.