Breaking boundaries and building materials layer by layer

When Milena Arciniegas talks about her work, she goes straight to the core: ‘What I do is chemistry, but combined with automation - we use robots to build new materials.’ Based at the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Genoa, the Colombian-born scientist is pursuing a bold new approach to designing and manufacturing materials.

For decades, engineers have faced the same challenge: different materials do not get along. Metals, plastics, ceramics - each brings unique strengths, but where they meet, the abrupt interface often cracks, fails, or corrodes. Arciniegas wants to overcome this. ‘In nature, our bodies already build materials with gradual changes in properties - think of bone blending into cartilage. That's what makes them strong and resistant. We are trying to replicate that graduality in artificial materials.’

Her vision is to create new families of "graded" nanomaterials whose mechanical and chemical properties shift smoothly from one side to the other. That could mean smartphones that last longer, implants that integrate better with the body, or even organ-on-chip devices that mimic real tissues for drug testing. The science is frontier territory because it does not just tweak existing materials - it asks us to rethink how materials are made.

And crucially, she does not rely on trial and error. ‘Most of the tools we use in chemistry today are the same as a hundred years ago - beakers, glass containers. But now we need to explore enormous chemical spaces. Robots can help us do that, not just by trial and error, but by screening combinations far more efficiently.’

Coming from a developing country, people don’t expect much. That means you have to be excellent, always.

Arciniegas's path to this research has been anything but conventional. She trained as a mechanical engineer in Colombia, worked on aerospace projects with Boeing in the UK, and only later found her way into chemistry and nanomaterials. ‘I went into industry-related research, but I missed science,’ she admits. ‘I missed the questions, the discovery. That's why I came back.’

Her international journey also meant navigating stereotypes and expectations. ‘I'm a Latina scientist working in Europe. From the beginning, I had to break stereotypes -how people perceive me because of the way I look, the way I speak, or my accent. Coming from a developing country, people don't expect much. That means you have to be excellent, always. Even in the smallest task, you need to show quality. That's how you stay in the game.’

That resilience is now part of what she tries to pass on. She regularly returns to Colombia, visiting her old university to tell students: ‘Yes, this is possible. You can start where I started and build a path in science.’

She laughs when recalling her teenage years in Barranquilla, a city better known internationally as the birthplace of Shakira. ‘She even came to my school to sing when we were teenagers,’ Arciniegas says. ‘Now, when people ask me where I'm from, I can say 'the same city as Shakira.’

Diversity is not just an add-on – it’s what allows us to build new things

Her lab today is a microcosm of her philosophy. Chemists sit alongside engineers, computer scientists, and automation experts. ‘One single scientist cannot do the science I do,’ she explains. ‘Problems are multifaceted, so solutions must be too. Diversity is not just an add-on - it's what allows us to build new things.’

Arciniegas's ERC-funded research is still in its early stages, but its ambition is clear: to change not just the materials we use, but the very culture of how we discover them. ‘What I want is to change the culture of how we produce materials - to bring automation into chemistry, so that scientists can spend more time on ideas, and less on repetitive trial and error.’

That mix of vision, hard science, and personal grit makes her not just a leader in frontier research, but a role model for anyone who doesn't quite fit the mould.

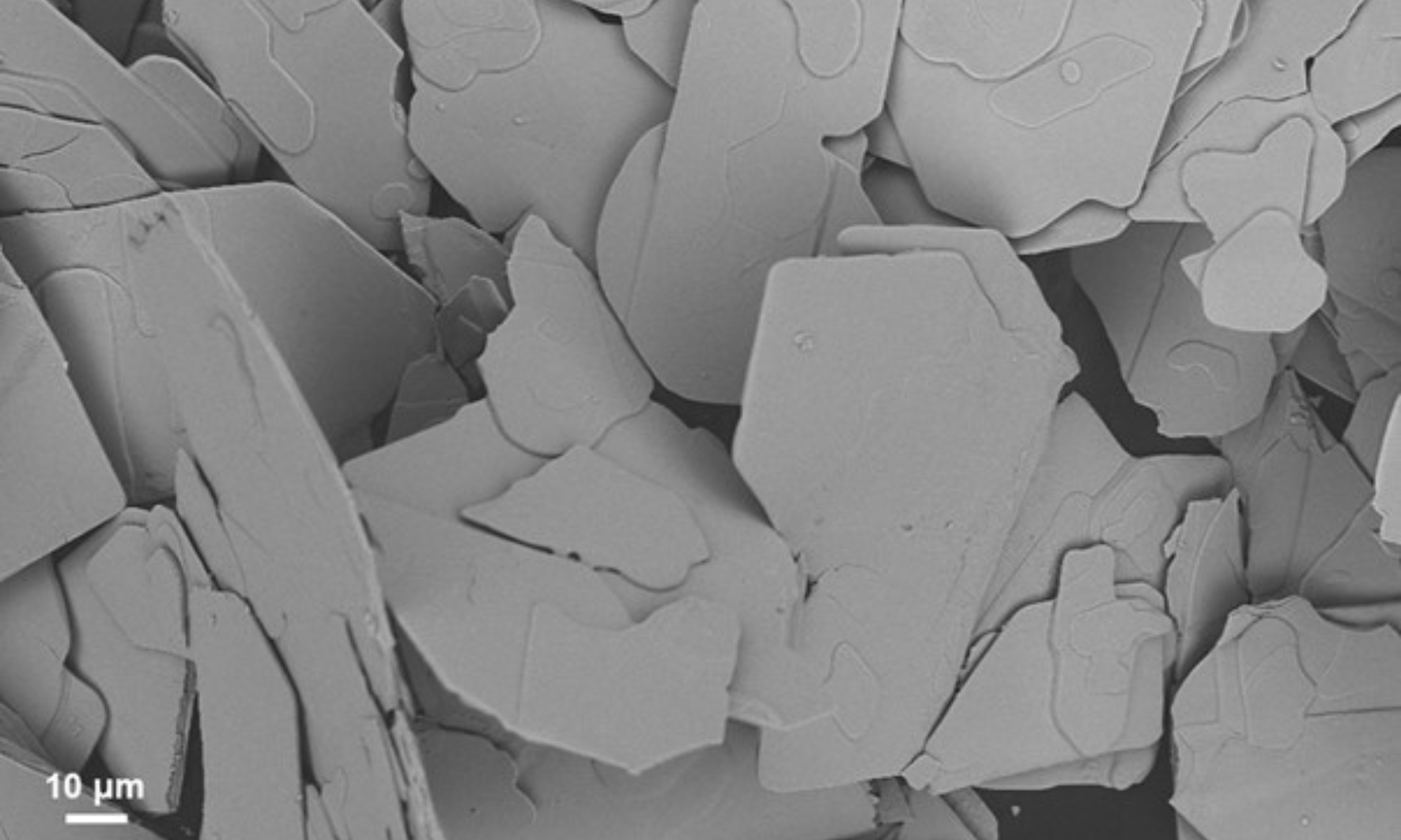

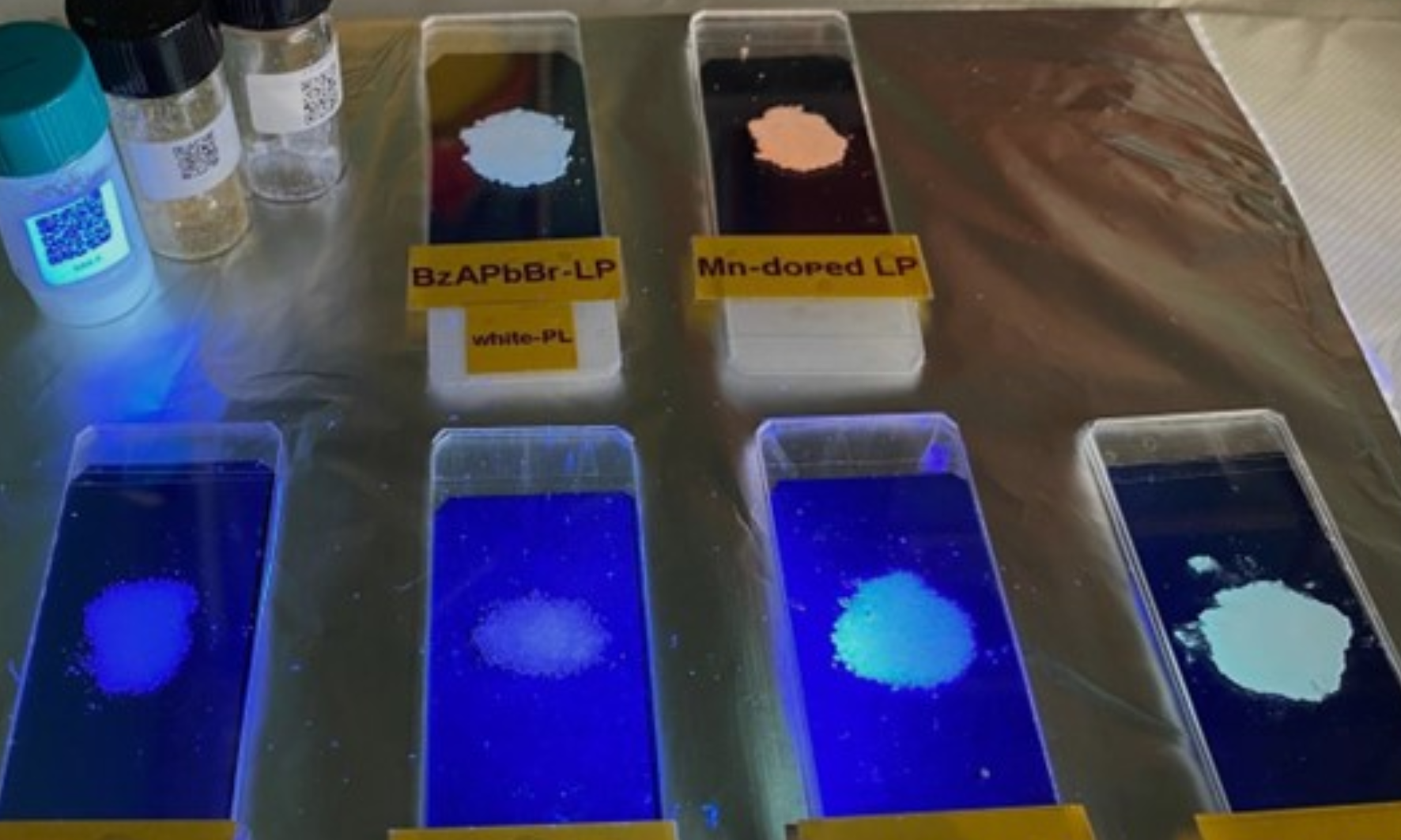

Milena Arciniegas, a Mechanical Engineering graduate from Universidad del Norte (Colombia) with a PhD from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (2008), founded a research group in 2018 on emitting organic-inorganic 2D layered structures. In 2024, she won an ERC Consolidator Grant to lead the Automated Nanomaterials Engineering research line, developing advanced functional nanomaterials through automated processes and data workflows.