Gut bacteria could hold key to new treatments

An ERC-funded project has significantly increased understanding of the crucial role that microorganisms in the gut play in maintaining health. The findings have since led to a patent, as well as a follow-on project that could one day steer the way to new targeted treatments for diseases, including cancer.

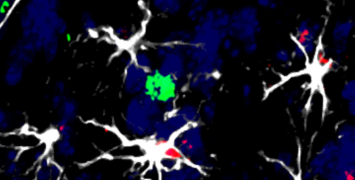

“Microorganisms present in the intestine, collectively called the gut microbiota, are essential to our health,” explains Maria Rescigno from the European Institute of Oncology in Italy, who led the DENDROworld project. “They break down larger molecules – like complex sugars – that we as humans are not equipped to degrade, enabling us to harvest more energy from food. They are also essential in the correct development of our immune system.”

However, alterations in microbiota composition – a condition called dysbiosis – have been associated with obesity, diabetes and cancer, although it is not yet clear whether dysbiosis is a cause or an effect of the disease. A key goal of the ERC-funded DENDROworld project was therefore to better understand exactly how microbiota is tolerated within the gut.

Breakthrough findings

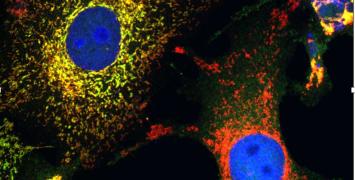

“We achieved two major results,” says Rescigno. “First, we found that epithelial cells –those that line the intestine – release a molecule called Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) that comes in two flavours; a short isoform, which is responsible for the establishment of tolerance, and a long isoform, which is responsible for the establishment of inflammation.”

Rescigno and her team found that the short isoform is expressed in the healthy tissue, while the long isoform is expressed only in inflamed tissue such as in atopic dermatitis and ulcerative colitis. This discovery opens up the possibility of using the TSLP short peptide to fight inflammatory diseases by re-establishing immune tolerance. This finding has since been patented.

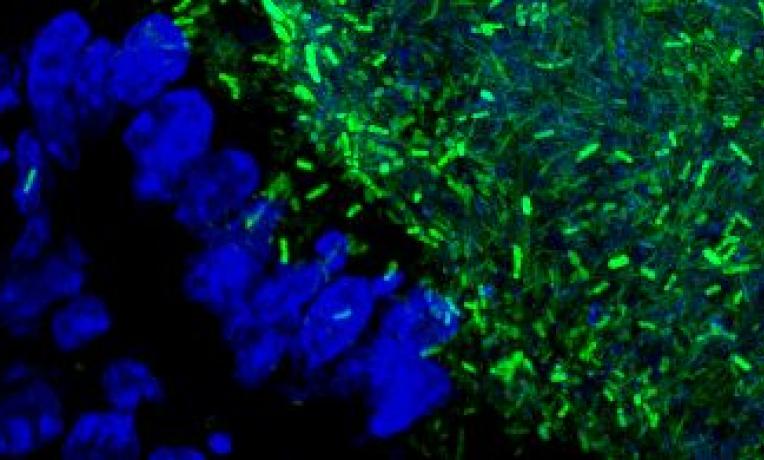

Secondly, the project discovered that the composition of microbiota is dependent on the amount and diversity of the mucosal immunoglobulin of the A type (IgA). “[This] is dependent on the amount of IgAs that is inherited and/or delivered by the mother through milk,” explains Rescigno. “This discovery has implications in the first phases of life, as it indicates that delivering IgAs early in life can positively impact microbiota diversity.”

As changes in microbiota composition have been associated with certain diseases, this finding could give new-born babies a ‘push’ in the right direction.

New research possibilities

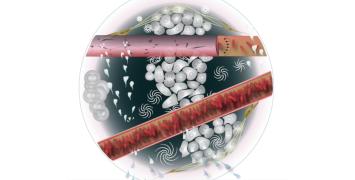

The project’s success has enabled Rescigno to launch a second ERC-funded project, called HOMEOGUT, which relates to the patented findings on TSLP. “We wanted to go deeper into understanding the mechanisms of the short isoform,” she explains. “Here, we focus more on what it is that enables our body to avoid microbiota from spreading. How do we protect ourselves and prevent microbiota from entering the blood stream, for example?”

So far, the project has demonstrated the existence of a gut vascular barrier, similar in structure to the blood brain barrier that controls the flux of molecules capable of entering the host.

“We found that this barrier is disrupted in coeliac disease patients who have liver damage,” says Rescigno. “We therefore successfully demonstrated a link between the gut and the liver that can be disrupted by disease. We are now evaluating the barrier in other disorders and whether this can be a new target of intervention in several diseases, including cancer.”

Rescigno is excited about the potential impact that this line of research could have in terms of developing new therapeutic treatments, and is certain that the progress she has made would not have been possible without support from the ERC.

“These grants are so crucial because they provide you with a stable financial situation for long-term projects,” she says. “Having an ERC grant increases your chances of receiving other grants from national and international agencies, and I am now professor at the University of Milan, on the back of being an ERC awardee.”