Could personalised neuroprosthetics make paralysed patients walk again?

Prof. Gregoire Courtine believes paralysed patients will be able to walk again.

This belief has represented the focus of years of work aimed at regenerating the functions of the spinal cord after injury. Thanks to his ERC funding in both 2010 and 2015, Prof. Courtine and his team have been able to develop so-called “personalised neuroprosthetics” that have led immobile rats, and more recently monkeys, to overcome their paralysis.

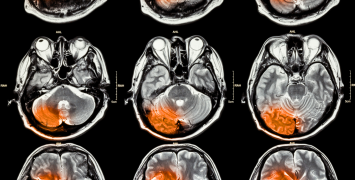

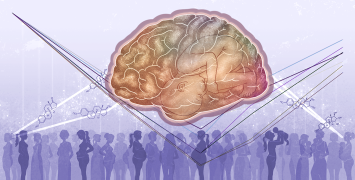

Fifty thousand people worldwide lose the ability to move their legs due to traumas to the spinal cord, and Prof. Courtine is aware of what the results of his work could mean for patients unable to walk. His research is based on the idea that the spinal cord already contains, within itself, the neuronal network to allow walking, despite being, in fact, controlled by the brain. When its ties to the brain are severed, for example after an accident, the cord alone should be able to generate movement.

This idea is fairly revolutionary for neurosciences, and an example of the “high-risk, high-gain” frontier research the ERC aims to nurture. Prof. Courtine was inspired to approach the issue from this different angle by working with the patients of the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation and listening to the Superman actor.

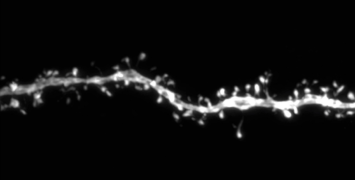

In order to stimulate the spinal cord to move, Prof. Courtine and his team developed implants to deliver drugs and electrical stimuli to the injured areas. This allowed for movement that was, however,involuntary. Therefore, work continued on a “robot” that could support the animal safely, allowing it to practice moving intentionally. Thanks to the apparatus, after relatively short periods of time, the animals that tested this method could walk again, even without the implants.

The right physiotherapy, achieved thanks to the supportive machinery and the correct stimulation had, in the animals that responded well to treatment, allowed a new connection to establish between the brain and the spinal cord. Prof. Courtine states: “This came as a surprise, even to our team. It showed an example of the incredible plasticity of the nervous system, and encouraged us to keep on”.

Although the extent of the consequences of this work for the treatment of human paralysis is still unknown - bipedal walking habits representing, for example, a new layer of complexity – there is no doubt that this discovery offers new hope for the future. In 2016, in fact, the team showed the revalidation could also work for primates.

The ERC funding allows the Professor to employ a multi-disciplinary team of young researchers, from physiotherapists to neuroscientists, neurosurgeons and engineers. It is this forward-thinking, highly qualified team that is at the basis of this great medical breakthrough

First published in the Annual Report on the ERC activities and achievements in 2016