How plants defend themselves

By Inge Ruigrok

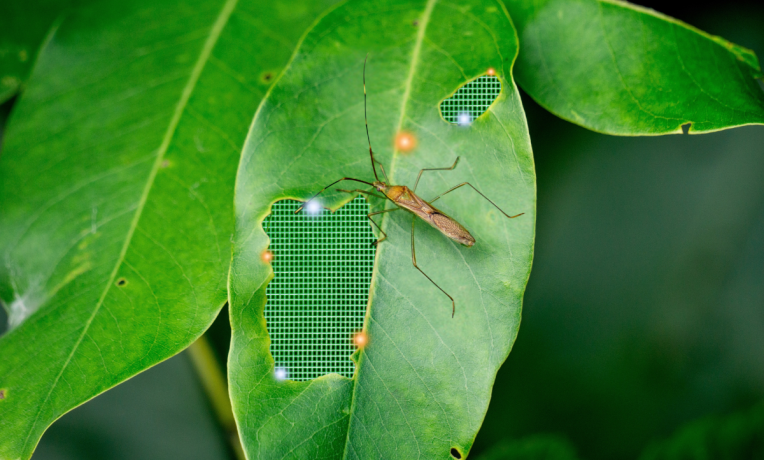

Every living organism- plants, animals, humans, even mosses clinging to bare rock - is under near-constant attack by what Peter Brodersen calls ‘parasitic genetic code’. Viruses are the best-known example: fragments of genetic information that can ‘condense themselves and take advantage of the host cell’s metabolism and molecular machinery to build copies of themselves.’

For life, this creates a fundamental problem. As Brodersen puts it: ‘It’s fundamental for any biological system to know the difference between what is my own genetic code and what is genetic code coming from the outside.’

We still do not fully understand how organisms solve this problem. In fact, ‘we don’t actually understand, for any organism, what all those layers of defence against this parasitic genetic code really are.’ But in plants, one defence mechanism stands out as central, powerful, and ancient: RNA interference.

RNA interference, or RNAi, is so important that it has already been recognised with two Nobel Prizes. For years, biologists believed they had a good grasp of how it worked in antiviral defence. Two enzymes were known to be essential. Genetically, they looked redundant - remove one, and the other could often compensate.

As Brodersen explains: ‘People think that the system operates or initiates with two different enzymes acting redundantly, so one can replace the other.’ But something did not add up. ‘I thought that was wrong. Not wrong because both enzymes were not required - they were - but wrong because why they were required had been misunderstood.’

Imagining the perfect defence

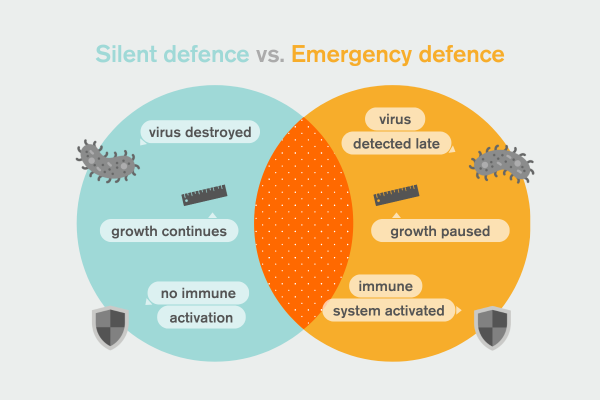

To explain what was really happening, Brodersen uses a simple but powerful metaphor. ‘If you have the perfect defence - in the abstract - you destroy the invader, and it doesn’t affect you otherwise.’

In this ideal scenario, the organism continues to grow, develop, and thrive. The virus is eliminated quietly. No alarm bells. No collateral damage. ‘You can keep happily growing; you just kill the parasite that wants to get in,’ he says.

This, it turns out, is the first line of defence. One branch of RNA interference does exactly this: it detects foreign genetic material and destroys it with extraordinary precision, without forcing the plant to change its behaviour at all. From the outside, nothing looks wrong.

But perfection has limits. What happens if the virus slips through? ‘Then the organism has a second option, but it is a costly one. What you can do is to start a war economy’, Brodersen says.

The metaphor is deliberate. A war economy keeps a country alive, but at a price. Growth slows. Resources are redirected. Life becomes harder. ‘A war economy is not good for you,’ Brodersen explains. ‘It costs something. You stop growing… the most important thing is to defend yourself right now.’

This is the second line of defence. It looks superficially similar to the first, but it is fundamentally different. Instead of quietly eliminating the virus, the cell reprograms itself. Normal growth is suspended. Immune pathways are activated. Survival takes precedence over prosperity.

‘That second opportunity looks a bit like the first one, but it isn’t really,’ Brodersen explains, ‘because what it does is reprogram you so that you focus entirely on defence - and you stop growing.’

Two enzymes, two jobs, two layers

This is the key conceptual shift: the two enzymes in RNA interference are not doing the same thing, as was assumed. ‘In fact, it is very, very different to have those two completely different layers', Brodersen says.

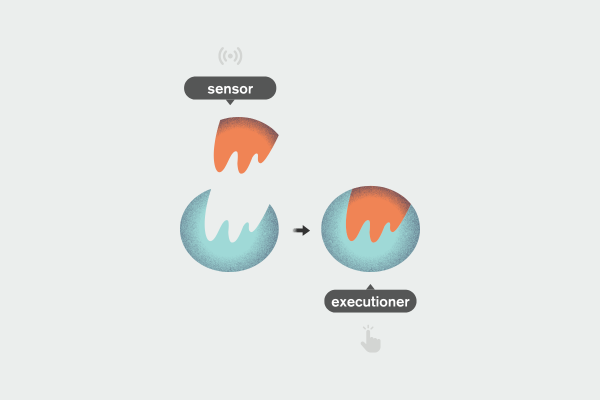

One enzyme operates the perfect, silent defence. The other governs the emergency response, pushing the cell into immune mode.

Even more striking is what happens at the molecular level. ‘You can use the components of this perfect first-layer defence and then repurpose them. They stop acting purely as executioners and start acting as molecular sensors, triggering what we would normally understand as the immune system, which I metaphorically described as going over to a war economy.’

Instead of simply destroying foreign RNA, these components become sensors, linking RNA interference directly to immune activation.

This system is neither rare nor recent. Evidence suggests it exists across the plant kingdom. ’Both flowering plants and all the way down to mosses - which represents a vast evolutionary distance - possess this kind of system.’

That distance matters. It tells us this is not an evolutionary accident, but a deeply conserved solution to a universal biological problem. While this work focuses on plants, the implications may extend beyond them. ‘I think you can argue that this is a principle that is probably much more broadly applicable in biology, even in other organisms.’

The idea that organisms reuse and repurpose existing defence machinery - linking silent antiviral mechanisms to full immune activation - may turn out to be a general rule of life.

Basal defence, not virus-specific

Does this depend on the type of virus? Probably not.

What Brodersen is interested in are what he calls ‘basal antiviral defence mechanisms’ - systems that act broadly and recognise invading parasitic genetic material in a general way.

These mechanisms do not detect virus-specific features, such as a particular protein. In humans, for example, immune systems can recognise the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. But such a response is highly specific to a single virus.

That is not what is happening here. Instead, these systems detect foreign genetic information itself – recognising that the way this code is formed, or functions differs from the organism’s own and therefore needs to be shut down. As a result, the response is unlikely to differ much from one virus to another.

Viruses evolve and mutate. This system is sensitive to intrinsic properties of foreign genetic code, and not to specific sequences or proteins. In that sense, it is largely immune to viral mutation.

Here, it is not what the code encodes that matters, but how it operates.

And that makes all the difference.

Science as it really happens

The discovery of two distinct antiviral defence strategies in plant cells did not come from following a straight line. It began with an experiment that failed to behave as expected.

‘One key moment I still remember clearly happened on a Sunday evening,’ Brodersen recalls. “I used to - and still do - play tennis on Sunday nights. That evening, I knew my first PhD student was in the lab, about to read out the results of an important experiment. I drove in after tennis because I was too curious to wait.’

‘We watched the data appear on the screen in real time. Then it became clear: this was not what we had expected. The experiment was meant to confirm something we already thought we understood. Instead, it showed something different.’

‘I remember driving home thinking through every possible explanation, checking mentally for missing controls. But everything was in place. That moment turned out to be a real turning point. In the long run, it led directly to much of what we are doing now.’

The big question that remains

With his recently awarded ERC Advanced Grant, Brodersen will build further on the results from his two previous ERC grants. The most ambitious question now is mechanistic: ‘How is it that this repurposed second layer of defence component is sensing the foreign genetic material?’

What exactly is being detected?

What molecules act as signals?

How does sensing turn into immune activation?

Early clues point to something new. ’There are good indications that the way this system activates the immune system involves totally new components.’ Small signalling molecules -‘signalling nucleotides’- may link RNA interference directly to immune receptors, opening an entirely new chapter in our understanding of intracellular immunity.

This understanding is important for solving practical problems in agricultural economies. Viral diseases in crops are devastating and, unlike bacterial infections, essentially incurable.

‘What you can do is burn the crops, basically. That’s especially problematic for perennial crops like orange or lemon trees, which take years to recover and become productive again. So there’s no doubt this is a serious issue.’

Understanding basal antiviral defence mechanisms - defences that recognise foreign genetic code itself, rather than specific viral features - could eventually change how we detect, manage, and prevent plant viral disease.

But Brodersen is cautious. ‘I don’t think I can sit here and say that if we get the answers, I know exactly how we can help farmers. That kind of translation to practical application can only come after we have the fundamental answers.’

‘It’s possible the solutions turn out to be simple. If we understand how sensing works and how nucleotide-based signalling triggers reprogramming into an antiviral state, we might identify a clear molecular signal that plants use to activate this response. One could then imagine monitoring when a viral infection begins and applying that signal to neighbouring trees so they can defend themselves.’

‘But it’s also possible that such a signal would be detrimental - slowing growth or even causing self-damage. At this stage, we simply don’t know.’

Biography

Peter Brodersen established his own group in 2011 at the University of Copenhagen where he has held a full professorship in RNA biology since 2020. His research focuses on post-transcriptional gene regulation mediated by small silencing RNA and covalent RNA modifications. His group has made several contributions to define molecular properties of the central players of RNA interference (RNAi), the ARGONAUTE proteins, and how the RNAi system is connected to innate immunity pathways. His group has also driven progress on defining biological roles of cytoplasmic N6-methyladenosine-binding YTHDF proteins in plant growth, and on deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying these functions.